I.

“How can a heart break twice?”

The local parish in Abba, St. Paul’s, is a big, angular building, pale yellow on the inside and unpainted on the outside. On the wide porch sat people on pews, listening to the Mass in progress, the burial service of Grace Ifeoma Adichie, the matriarch of the town’s most respected family. The compound was packed with vehicles, in rows allowing for easy exit, because down the road, a seven-minute walk from the church, is the Adichie family house, where, after Mass, all must proceed. Service ended and procession began. Behind the white coffin, before relatives in uniform ankara and a long, long line of priests in violet chasubles, walked the family’s youngest daughter, Ngozi, the woman the world came to know as Chimamanda. If you never knew her face, you would not now, not because of her white nose mask but because here she moves not as the most famous Nigerian alive but as a daughter of the soil, someone you saw every day. She walked with her elder sisters, Uche and Ijeoma, the trio in white lace and peach silk satin headbands, bearing bouquets of flowers, regal in mourning.

It was May, and mourning was all she had written about in the previous twelve months. Last June, their father, Professor James Nwoye Adichie, died, from complications from kidney failure, and Chimamanda, in the public stare, threw herself into a full rite of grief, writing about places in her that she had never written about, her hurt, her rage at the world. His stories of surviving the Biafran War inspired her monumental second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, the book that taught many young Nigerians about the tragedy and made her a household name. His death changed everything and struck in her an unfillable gash. They’d spoken the night before he died, and his last words to her were “Ka chi fo.” Good night. After he died, every Sunday, for months, their family got on Zoom to see each other, talk to each other, console each other. Then in March, on their father’s birthday, a day the family already anticipated in pain, their mother died, too.

This church was the third-to-last place that Grace Adichie stepped foot in. She returned from work in Awka, the Anambra State capital where she sat on the state education board, and came here for Stations of the Cross on her last Friday, and on Sunday again for Mass, and that evening she was unwell, and she was driven back to Awka, to a private hospital, and she spoke to her children, and the following day, her recovery took a dip and she was moved to a teaching hospital. “Do my children know that I am being transferred?” she asked, confused. She was 78.

Chimamanda and her sisters walked behind the ambulance, eyes stoic behind the masks. In many ways, this was the entire basis for Chimamanda’s world. She introduced her mother, in her essays and talks, as her first feminist influence, the woman who chaired a university committee and refused to swap “chairman” for “chairwoman” because both titles were the same job, the woman from whom she took her first fashion cues, including dressing superbly for church. She’d written about withdrawing from the performance that religion became, and falling back in love with the Church’s opulent traditions when Francis I became Pope. Treasuring family and being Catholic are the fabric of her first novel Purple Hibiscus, the 2003 book that marked a new turning point in African literature, a tender story of love and rediscovery that brought many Nigerians — including most of the younger writers who were at the burial to support her and were now watching the procession from the porch — the simple revelation that their modern lives can be shown in books, too; that they can tell their own stories with fidelity to specific experiences and it could come alive, too.

It felt, as Chimamanda walked, like more than just the end of a time for her. Her fiction, memoried by her father, lunged her into recognition, but it is her feminism, substantiated by her mother, that flung her voice further afield, enabling many women to reclaim their own places in the world. Losing both meant that half of her own world had been pulled from her feet. In her public acknowledgement of the news, she wrote: “How can a heart break twice?”

II.

“Do you know how many people died here?”

James and Grace Adichie lived most of their lives in Nsukka, a little hilly Igbo town with deep history, perched on the northernmost, cold tip of southeastern Nigeria. It is the site of the University of Nigeria, the country’s first indigenous and Africa’s first land-grant higher institution, opened a week after it gained independence in 1960. That year, James graduated top three in his class in Mathematics at the University College, Ibadan, then affiliated to the University of London, and returned home and met Grace, and began lecturing at the new school. Seven years later, after a mostly Igbo-led coup and a Northern countercoup and the pogrom of the Igbo in the north, the late military leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu declared the secession of Biafra, and, as nearby Enugu became the new capital city, the school in Nsukka was renamed the University of Biafra, and in its science labs, the ogbunigwe, the bomb that became the blockaded Biafrans’ greatest weapon, was manufactured by staff and students.

In July 1967, weeks into the war, Nsukka fell. Shortly after, Chukwuma “Kaduna” Nzeogwu, a leader of the first coup, was killed on the outskirts of the town. When Federal soldiers entered, they went straight to the campus, to the departments, the libraries, and burned books and notes. It was an equivalent of salting the earth, a deliberate destruction of ideas, of Igbo resistance. It lasted 30 months. An estimated three million people died, mostly children, mostly from hunger.

After the war ended in 1970, Igbo people who had bank accounts were given £20 irrespective of what they had in their accounts before the war; their property were seized in some parts of the country; there was a ban on imported clothing, on stockfish, trades they could potentially use to find their way back; and the government announced the indigenization decree which shifted corporate and industrial control from foreigners to Nigerians, creating new wealth that the robbed, broke Igbo could not partake in. The official and unofficial policies of repression made the Igbo disbelieve the post-war slogan of “No victor, no vanquished.” And so the idea lived, renewed, burning. As people who’d fled back home for safety left again, academics and artists and thinkers, the survivors, gathered again in Nsukka.

It was a second phase of creativity in the campus, a golden one, with great innovators in the arts and sciences, from Chinua Achebe to El Anatsui to Alexander Animalu, and birthing such definitive movements in African arts like the Nsukka Group. Nsukka, once again, was emblematic of an Igbo dream of Nigeria: a place of quality and equality and fairness.

It was at this time that James, who returned to the country just before the war and worked in the Biafran Manpower Directorate, resumed teaching in the campus. Seven years after the war, in 1977, James and Grace had their last daughter, Ngozi, in Enugu. Things moved well for the family. Grace rose to become the university’s first female registrar, and James, the first Nigerian to get both a Ph.D. and professorship in statistics, became Deputy Vice Chancellor, and later helped establish the National Centre for Mathematics in Abuja. His title was “Odelu-Ora Abba”: One Who Writes for Our Community. James was acquainted with Achebe, who lived on campus for some time, and when the novelist left, James was given his former home.

Ngozi grew up a boisterous girl, popular with mates, brilliant in class, and earmarked to study Medicine. But she preferred stories. She was reading Enid Blyton novels and began making up stories in which her characters had blue eyes like the white people she saw in books. It was not until she read Things Fall Apart that she knew that people like her, African and Black, could exist in fiction. She read Weep Not, Child and Joys of Motherhood and swept through the African Writers Series. She was a romantic and spent hours in Mills & Boon titles.

By 13, she had a habit of analyzing her father’s stories, what he said about Biafra. James’ brother, Michael, fought in the 21st battalion of the Biafran Army, and his brother-in-law, Cyprian Odigwe, fought with the Biafran Commandos. His father-in-law, Aro-Nweke Felix Odigwe, whom he never met, died in the war. As did his own father. After the war, when people could move about again, James traveled to Nteje, where there was a refugee camp, to find his father’s body. The officials looked at him like he was mad. “Do you know how many people died here?” they told him. They pointed at the mass grave: “Somewhere there, that’s where we buried the people.” James wept afresh, and then he, a very practical man, took sand from the mass grave and brought it home to Abba. It was not enough to fill the hole in his heart and, occasionally, he let out memories, and Ngozi would be there, at his feet, listening, asking questions.

In Abba, she saw buildings bullet-ridden from the war; when she played with other children, they sometimes came across rusty pieces of ammunition. People spoke about loved ones who never made it back from the North. Even in her distance from the war, its memory hung over her. “Agha ajoka,” James would say after each story. War is very ugly. But, he would also add, what mattered was not what they suffered but that they survived.

Ngozi was 20 when she published her first attempt at a book in 1997, a poetry collection titled Decisions. It was juvenilia, prosaic verses on politics, religion, and love:

Like a child at a den

Owned by a starved lion,

Or a thief caught

In petty pilfery,

At a standstill

My country.

The next year, she wrote a play, For Love of Biafra, in which the heroine Adaobi, in love and in the pressure of war, amplifies her strong will. She was retracing stories she heard from her father, how they survived, what they learned.

In 1998, a year into her Medicine and Pharmacy degree in Nsukka, she left for the U.S., to study Communications and Political Science at Eastern Connecticut State University. She lived with her elder sister, babysitting her nephew in the day and writing at night. She wrote her first short stories with her baptismal name, Amanda. Then she attempted a novel. It was a cloying, overwritten thing and she hid it away. Then came homesickness, a churning for the familiar. She decided to try her hand at another novel.

She was 24 when she began Purple Hibiscus, writing from the yearning in her heart. It was a story about a family ruled by an iron-fisted patriarch, Eugene Achike, a newspaper publisher and staunch opponent of the military government who in public is a philanthropist, a model in their Catholic community, but at home is an abuser, a religious fundamentalist who discards his own father for being a Traditionalist. The story is told by his daughter, Kambili, a shy girl growing into her own, observing her mother, Beatrice, and her brother, Jaja, and falling in love with a priest, Father Amadi. The family lived in the city of her birth, Enugu, but their awakening would happen in Nsukka, where the narrator’s aunt, Ifeoma, is a lecturer and her family, daughter Amaka and sons Obiora and Chima, even without a living father, is joyful. The prose was poetic, making myth out of the characters’ surroundings. If you have ever been to Nsukka, you might feel an envelope of magic in the trees, the market, the school. You might sense a permeation by a livewire history. She soaked her first novel in all of these.

“Someone whose voice seemed molded just for us”

It is now well known that the pungence of Purple Hibiscus struggled to attract literary agents. It was the turn of the millennium and, in American and British publishing, the trendy non-White writers were Indian, not African, and the other hot books by writers living across cultures were set where they lived, not where they came from. This 25-year-old from Nigeria and her manuscript were none of these. Even though she was influenced by the great Achebe in philosophy, her prose was different, her storytelling more detailed, the hand of a writer wisened with style, who had enough audacity to sprinkle an African language, Igbo, in her dialogue.

One agent asked her to use the “African material” as background for a continued story set in America. Another scrawled a giant NO on her query letter and sent it back. Finally, Djana Pearson Morris, an indie agent in Washinton, D.C., wrote back: I am willing to take a chance on you.

One evening, as Ngozi lay in her brother’s guest room in London, an idea came to her, an Africanisation of her English name Amanda to Chimamanda, Igbo for My God Will Not Fail. She shared the long name with her agent: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

It was the summer of 2002 when Antonia Fusco, an editor at the indie press Algonquin Books, received the manuscript. Morris’ pitch was honest: the book, she wrote, was not a commercial novel, but it was one of the best first novels she’d read.

“The pitch was the novel,” Fusco, who left publishing and now works in the New York City education system, remembered. “From the very first page, it was clear that you were in the hands of a sensitive and graceful writer, one who, with very few words, created a narrative intimacy between the reader and her characters. All my colleagues unanimously agreed at our editorial meeting: We had to acquire this wonderful novel by this new talent.”

Elizabeth Scharlatt, then the publisher at Algonquin Books, also recounted details to me. “I remember Chimamanda coming to the office in New York. She seemed nervous, a little shy — or was it wary? I have no idea if the book had been turned down by other houses before she came to us, but we didn’t hesitate.”

Fusco told me that Adichie being African was no problem. “We thought this was what made this first novel unique. What many publishers would see as a challenge, we saw as an asset.”

Scharlatt reflected on the book’s chances. “As a small indie press, Algonquin was not driven by market trends or shareholder pressures,” she said. “We were committed to launching a debut novel every season. And because our list was small, we were able to put all our muscle into promoting Purple Hibiscus, and Chimamanda. Publishing it might’ve been something of a risk at the time — launching any new writer is a risk — but we were drawn to her writing and her story. I sometimes wonder if Purple Hibiscus might’ve gotten lost on a large list; at Algonquin, it was our sole debut novel for the Fall 2003 season.”

The Algonquin Books team was experienced in marketing debut novels. “The strategy,” Fusco said, “was to get word-of-mouth support among booksellers and media through advance reading copies, with personal calls from our sales and marketing directors who were equally enamored of this novel. We also sent her on a tour, as we discovered that she had a gift for public speaking even back then.”

Algonquin’s then publicity director, Michael Taekens, was adept at getting review attention, and soon the press secured a crucial endorsement: Jason Cowley, a Booker Prize judge the year Arundhati Roy won, wrote an advance blurb calling Purple Hibiscus “the best debut novel I have read since Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.” It was re-ignition, and only a day after Algonquin sent the manuscript to U.K. publishers, Fourth Estate made a pre-emptive offer.

The editor who made the offer was Mitzi Angel, now the publisher at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. At the time, Angel had only acquired one or two books for Fourth Estate, and she saw a bound galley of Purple Hibiscus in their London offices. “I felt the power of that first sentence,” Angel told me: “Things started to fall apart — possibly a nod to Chinua Achebe.”

In 2004, Purple Hibiscus came out in the U.K. and made the Booker Prize longlist. But it was its inclusion in the Orange Prize shortlist that turned heads. “Debut novel from Nigeria storms Orange shortlist,” ran the headline by The Guardian, which had not even then reviewed the novel:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has fought her way to the final heat of the £30,000 Orange award, defeating more than a dozen highly tipped and experienced authors. . . the most formidable shortlist of any book contest this year — a list stronger in depth than at the final stage of either the Booker or Whitbread prizes.

“I was very pleased but I was not surprised,” Fusco told me. The immediate U.K. success “helped us to build momentum in the U.S.” Later, Purple Hibiscus would win the Commonwealth Prize for Best First Book. Scharlatt told me that it was translated in more than 40 countries, including Korea and Japan. “Her vividly drawn characters,” Scharlatt said, “transcended ‘place.’”

Back home in Nigeria, there was palpable excitement. Here was a book that stunned on a visual level, with sensory detail like nothing before it. Kachifo Limited launched its Farafina imprint with the Nigerian edition of the novel, and organized a reading, driven by the curator Ebun Feludu. The event’s success has been credited with spurring the N.L.N.G.’s oil-moneyed entrance into Nigerian literature and sciences.

The editor Anwuli Ojogwu, who proofread Purple Hibiscus as an intern at Kachifo, remembered going on book tours with Chimamanda when Half of a Yellow Sun came out in the country. “At this particular event, at Jazzhole in Lagos, after a reading, a journalist asked her, ‘Why do you look so feminine?’ I remember she laughed and I think asked why not. Then, journalists looked at her curiously. A young, beautiful and talented woman, who always looked delicate, well dressed and graceful. And I don’t think they could reconcile her feminine image with literature where being radical is synonymous with the writer-artist. But since then she has gone ahead to express her interest in fashion and redefined the feminine image in the literary scene.”

There was also, in her Nigerian reception, an unspoken age factor. Confidence was associated with older writers. Nigerians had known Flora Nwapa and Buchi Emecheta, but Nwapa and Emecheta were mother figures, and Chimamanda was young, 26, and exploring a subject Emecheta explored: marital abuse. From the page, the book had been embraced, but now in person, she was intriguing.

With its flow, accessible language, and dramatic story, Purple Hibiscus moved onto secondary school reading lists, but would not really take off in universities until her bigger novels. And it was also being heavily pirated.

Ojogwu, now her Nigerian publisher at Narrative Landscape Press, told me, “When Half of a Yellow Sun was released, we made good record sales, but books were not exactly flying off the shelf. She wasn’t filling the halls for readings — they were not full to capacity until Americanah. Now her work sells more as a collectible, as a bundle, than as single copies. She has come a long way and embedded herself solidly in our cultural imprint.”

A few more years in America, a Hodder Fellowship at Princeton and a MacArthur “Genius” Grant later, Chimamanda, after Half of a Yellow Sun, collected her stories, spread in magazines, in The Thing Around Your Neck, which served as a bridge to an era to come, the turn in tone and subject that Americanah was. Americanah won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction in 2014, but it was the year it came out, 2013, that recalibrated her career: it took the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize, shot up the charts when it was named a New York Times Top 10 Book of the Year, and then Beyonce released “***Flawless,” sampling her “We Should All Be Feminists” TEDx Talk from 2012.

Before Chimamanda, being featured by Beyonce would have been, for an intellectual, the Everest of popular accomplishment. But, grounded by her solid body of work, she made it a stepping stone to a wider audience beyond book readers.

There is a categorizable way to look at her storied rise. Her first iteration was the bright teenager who produced a play and a poetry collection, both juvenilia, still searching for her footing but already ambitious in her worldview. The second was the successful storyteller with a new name, who in her 20s wrote two classics and was recognized by Chinua Achebe as one that “came fully made.” The third, born in her “The Danger of a Single Story” TEDx Talk in 2009, was the multimedia signifier, venturing into nonfiction, suffusing logic with storytelling, and utilizing the ubiquity of video, and image, to reframe conventions. The fourth was the icon, introduced to a broader audience by the Beyonce feature and enthusiastically received in American liberal media, fashion, and celebrity circles, becoming a commencement speech fixture in Ivy League colleges, becoming the face of British brand Boots No. 7, her words worn on runways, recited for women’s empowerment campaigns, referenced in movies. We are witnessing the fifth, the cultural connector who belongs to literature only in job description, who has shared stages with Hilary Clinton, Michelle Obama, and Angela Merkel, who became the first woman on the cover of PORT and joined 14 other women on the September cover of British Vogue guest-edited by Meghan Markle, who in Lagos hosted Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri for the Nigerian fashion community and Lupita Nyong’o for the film elite.

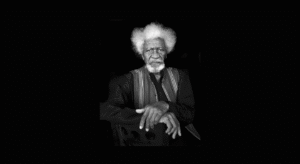

Self-reinvention is her turf. Her transition from bestselling author to pop culture icon was, in her geographical and generational milieus, uncharted territory. She is a writer but her words, already translated into 30 languages, charted on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 years before Nigeria’s Afropop acts. The Half of a Yellow Sun film from 2013, an international high for Nollywood, was hotly anticipated on the strength of her name recognition. She is not a video artist but hers — the ankara, the hair, the telegenic grace and quiet authority — is one of the most distinct, and duplicated, images out there. Not since the trio of Chinua Achebe, Fela Kuti, and Wole Soyinka has a Nigerian artist commanded such attention. She inherited a male-centric legacy, and raised the bar. The drawback is that talk of her cultural status surpassed talk of her literary artistry.

Yet none of this would be possible were she not a detailed storyteller, a genius of long fiction. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novels are possible not simply because she is a remarkable crafter of sentences but because those sentences have a beating heart full of humanity, her characters demonstrating as much logic as emotions to feel like real people. It is a rare combination, the ability to understand people and situations, to bring them all into the imagined, and when the story goes grave, to soften it with humour.

Arinze Ifeakandu, a graduate of her workshop whose story collection God’s Children Are Little Broken Things comes out next year, first read Purple Hibiscus as a teenager. “I’d been imitating, first, Achebe, then Buchi Emecheta, but immediately replaced them with this new rhythm,” he told me of Adichie’s influence on his work. “We’d found someone whose voice seemed molded just for us. I wanted to write something worth claiming.”

Because of Purple Hibiscus, Ifeakandu went to university in Nsukka, where he, like many younger writers, now sets some of his fiction. “Adichie made Nsukka, a place already steeped in history and legend, into a lore. Walking on campus with friends, we would come upon a street and say, ‘This street is in Purple Hibiscus!’”

He sees Adichie’s Nsukka as a microcosm of Nigeria. “Nsukka is ideal, a place of safety and spiritual resistance—from Kambili to Ugwu, to Ifemelu and Obinze, in Nsukka everyone seems freer and in love. Outside Nsukka, the disruption happens: a violent father descends, war becomes heated, people grow up and life becomes all too real. Nsukka itself is at risk of having its serenity destroyed, either by invading federal forces or by the effects of corruption. There is pre-war and wartime Nsukka of the ‘60s with its sweeping optimism and faith—the conversations in Odenigbo’s living room, the audacious energy of a new nation’s upper middle-class, their idealism—and there is Military Rule Nsukka of the ‘80s and ‘90s where the conversations have become practical: the country did not live up to expectations. The sheer range of that body of work. Adichie has given us something invaluable in addition to great art: she has told the story of our country in three timeless novels.”

III.

“Grief is this”

It is a Friday in February, little over two months before her mother’s burial, when I arrive at Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s house in Lekki, Lagos. The house is big and square and the sitting-room is spacious, the furnishing homely, as if chosen to house memories. A TV shelf covers a wall, with books, framed photos, and a replica of a Benin bronze head. On another wall, a work by the rising Nigerian artist Marcellina Akpojotor. On the table, a small pile of big books: Cartas Apasionadas’ The Letters of Frida Khalo, a book on the painter Obiora Udechukwu, Carrie Mae Weems’ The Kitchen Table Series, and the Obamas’ memoirs, Becoming and A Promised Land.

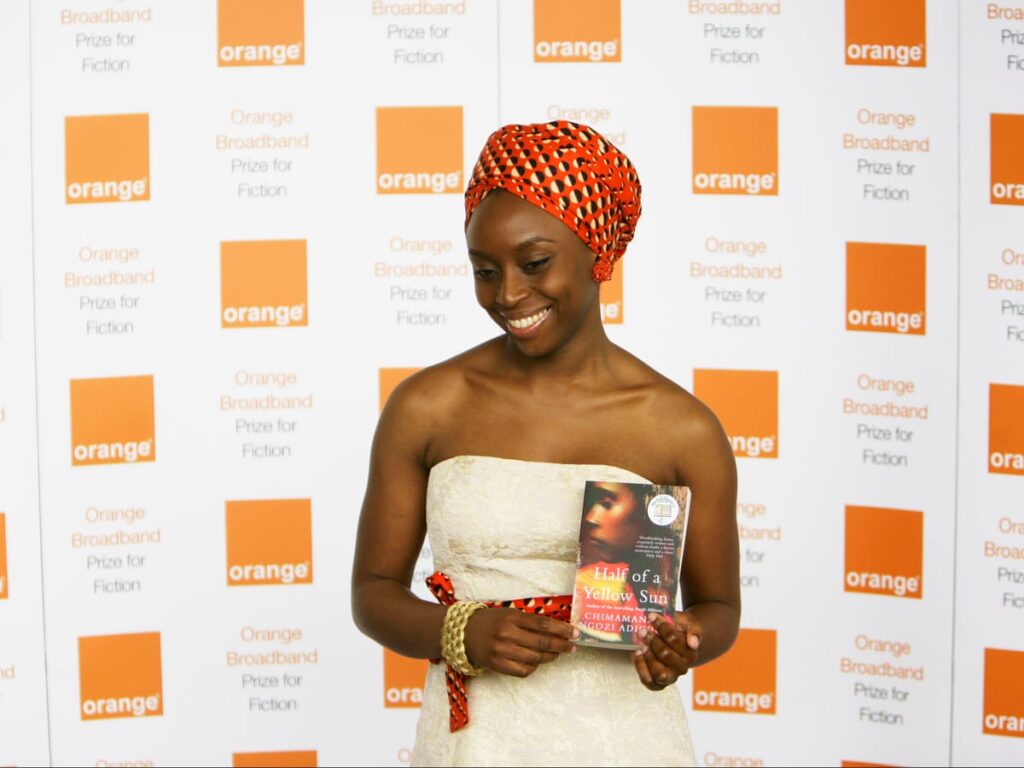

Last year, Half of a Yellow Sun was named the Women’s Prize’s “Best of the Best” in the award’s 25th year; it previously received a version of the honour in 2015, as the best winner of the prize’s second decade. She might not be hung up on prizes but this one has been essential in her ascent. Winning it as a 29-year-old in 2007, when it was the Orange Broadband Prize, jolted her career, and her other novels have been shortlisted for it. For weeks now, she has been on Instagram, on a read along with her one million followers, answering questions 15 years after the book came out.

When Chimamanda, rocking a black halo of hair, descends the stairs with her trademark almond-eyed, full-teeth smile, her presence fills the room. She is wearing the green T-shirt she designed herself; it says Omekannia, Igbo for Father’s Daughter. She is still in mourning, eight months after her father’s death.

“June 10,” she says the date, gazing upwards. It is pain and she is dealing with pain the way we all tend to do: turn away. “Pre-June 10, I was different,” she tells me. She is still unaccepting, still resistant. “Yesterday was a very tough day for us, my brother, my mom,” she sighs. “Grief is this: some days you’re fine and other days you wake up and you can’t stop crying.”

Last year, she wrote a long essay mourning him in The New Yorker, and this year it came out as a chapbook, Notes on Grief. “Grief is a cruel kind of education,” she writes in it. “You learn how glib condolences can feel. You learn how much grief is about language, the failure of language and the grasping for language.” She adds, “There is value in that Igbo way, that African way, of grappling with grief, the performative, expressive outward mourning, where you take every call and you tell and retell the story of what happened.” In Half of a Yellow Sun, she wrote: “Grief was the celebration of love, those who could feel real grief were lucky to have loved.”

She usually told people in mourning to take refuge in memories, and she might be doing so now: remembering her father playing sudoku, visiting her in the U.S. and always turning off the radio. He’d shown her many things: that learning never ends, and that she, as a woman, did not need the approval of men. He affirmed her, called her “Ome Ife Ukwu,” Doer of Great Things; “Nwoke neli,” Equivalent of Many Men; “Ogbata Ogu Ebie,” The One Whose Arrival Ends the Battle. He was also a staunch defender of his wife, Grace, so that Chimamanda nicknamed him D.O.S.: Defender of Spouse. “How can?” Grace is said to have asked, stunned, when she learned of her husband’s passing: “But he didn’t tell me anything.” They were that close.

The Adichie family are not mourning only their patriarch, though. Three months before his passing, they lost Chimamanda’s favourite aunt, her mother’s younger sister Caroline, to brain aneurysm. And then a month after his passing, his only sister, Rebecca, followed, in the same hospital as her brother.

One immediate result of her loss is that she is opening up more. She has previously admitted to living with depression, and last year, she wrote about suffering concussion, having slipped and fallen in her home. This year, she stunned Nigerians by sharing that the name “Chimamanda” was invented by her. Since publishing “Zikora” months ago, a short story on Amazon Prime in which a woman goes through childbirth, she might have felt a little eased. She is writing a few other pieces at the moment, on a range of subjects: another story for an Amazon Prime speculative fiction anthology, set in a world ruled by The Matriarchy, and an essay on her personal experience of gender. She is also working on CNA4, that fourth novel, and the process is one she is getting into full rhythm for. It is now eight years since Americanah came out; there were seven years between it and Half of a Yellow Sun, so she is on track, even if that’s not what her fans want to hear.

Each of her books had a secondary reason to exist. She wrote Purple Hibiscus to dispel the ghost of that first “not very good” novel manuscript; The Thing Around Your Neck because her publisher needed to collect her stories; and Americanah because she was tired of being a dutiful daughter of literature. But Half of a Yellow Sun was different. It called her from the moment she was able to think as an adult; it called her and drained her. It imbued her with an even greater hunger for her history, and she enrolled for an M.A. in African Studies at Yale, where professors discussed her book and she sat in the classes, weirded out, pretending she didn’t write it.

Her chef, G., returns, a young man in white, and Chimamanda lifts her glass, “Are you sure you don’t want orange juice?” I accept this time. She keeps her glass on the table behind the long cushion she’s reclining on. She says, “First, tell me about yourself.” It is what she does: interview her interviewers. “It’s your story that’s interesting,” she says with a comic roll of eyes, the trolling humour of someone who has been asked too many silly interview questions in her life and is now taking precaution. I laugh, and I tell her how, in June 2012, in my second year as an undergrad in Nsukka, I began reading Half of a Yellow Sun and midway through it, I closed the book and walked around Mbanefo Hostel and realized that my life had changed, that I would ditch my dream of becoming a history professor and want to write seriously. (I don’t tell her that in secondary school, a junior gave me a copy of Purple Hibiscus and I rejected it because I didn’t like the cover.) “This story,” she says, “I find it very moving, really.”

A young woman comes in with a child, and Chimamanda beams. She calls into the house, for her daughter: “Come say hello to Aunty!” She opens her hands for the boy, her nephew: “Nna m. Hey Baby, nna m, bianu.” A peck: Mwaa! Her daughter shows up, lighter-skinned, bouncy and chubby cheeked, with a self-assuredness I imagine her mother might have had even at five. (She once covered her mother’s eyes as she watched a video of her grandfather. “I don’t want you to watch the video of Grandpa because I don’t want you to cry,” she told her.)

Chimamanda kisses her daughter’s cheek. “This,” she holds her, eyes closed as she inhales, “is the love of my life.”

“My father adored his father. This father he adored died in Biafra”

Since she finished the book sixteen years ago, Chimamanda hasn’t read Half of a Yellow Sun from beginning to end; she doesn’t read her work once published. “I read the bits that I have to read in public,” she tells me. “But so much time has passed. Reading it this period was actually — it was a very strange experience. I don’t know, it made me — there’s a part I’ll get to and I’ll be like, ehen, so I wrote this?” She laughs.

And yet every time she opens her work, in public or in private, there is a version of her that is intensely self-critical. With Half of a Yellow Sun, “There are parts I’ll read and I’ll be, like, hmmm, I’ll do it differently today. There are passages I’ll see and I’ll think, oh, no, this is a disaster, I do not like these sentences, I would totally redo them. Then there are parts of the book, yes, I wrote them, but that I feel deeply moved by.”

She has said it over the years and she tells me the same now: it was a deeply, deeply emotional book to write. Now that her father is gone, reading it, and remembering which parts came from his stories, is poignant enough to make her cry.

“It’s so funny what that book has become,” she breathes, “because I remember writing it and I remember my dear Binyavanga telling me” — she breaks off, a look of anticipation, a pointing finger — “did you ever meet Binyavanga?” I tell her I only once spoke with him on the phone, forgetting that I edited two of his essays. She shakes her head slowly: “You know, the world lost a beautiful man, a first-rate brilliant thinker and writer, we lost, ah,” she sighs, finally giving in to the relived pain in her voice.

They met in the early years of the Internet, in an email group for writers, where an American directed her to “the other African,” and they got talking and found a shared love of Camara Laye’s The Dark Child and a Pan-African understanding of arts and politics. They met in person for the first time in 2002, at the Caine Prize ceremony in London, where they were both shortlisted and Binyavanga won. The following year, he used his prize money to fund the Kenya-based organisation Kwani?, becoming its founding editor and, long after he left the role, a singularly galvanizing presence in the continental scene.

Remembrance, for Chimamanda, is about the joyous. But Binyavanga’s death, in 2019, after a series of strokes, pains her afresh, and it feels, for a moment, as if the great Kenyan writer were in the sitting-room, hair multicoloured, shirt a burnished indigo, skirt a bright pink, filling the rest of the couch, needling her with arguments. It feels as if, in the space of her sigh, he lives again. I feel that, in Binyavanga, she lost not only a beloved friend but something of a moral partner, a divergent but complementary force. Not many people get to have that.

“I remember Binyavanga saying to me, with just shock and — he said, ‘How can you write a novel about the Biafran War?’ I said, ‘Well, I am.’ Then I remember he said, ‘But will it be balanced?’ I said literature — literature has no business being ‘balanced.’ If you want to ask me if it would be truthful, will it be emotionally truthful — but ‘balance’? And Binyavanga — who again is a person of such great wisdom — even when we disagree, I listen to Binyavanga.”

Even though she responded strongly in defence of her need to write the story, she had misgivings, uncertainty in how it would be received. When its Nigerian edition came out in 2007, her publisher, Muhtar Bakare (“God bless him”), told her, “You have to be prepared for anything.” It was important to Bakare that Nigerians told the stories of their history, but he needed to prepare her.

“To say that I had misgivings is not to say that I ever thought about not writing the book,” Chimamanda tells me. “Ever. This is something that I’ve carried in my soul since I was, I don’t know, 14 years old. I can’t intellectualize it. A lot of these conversations I have, I have to make up things. I cannot tell you why. I don’t know why. All I can tell you is for as long as I became a thinker in a grownup way, which was around 13 because I was reading books I had no business reading, I’ve been taken by our history. I’ve just always been that child who looked back, because I wanted to understand what was behind us.”

Her sense of responsibility came not from inherited trauma but from the constancy of memory. “My father could tell you 20 stories about our grandfather, who we never met. My father adored his father. This father he adored died in Biafra. It’s not just that he died, it’s that he died and my father couldn’t go to bury him. It’s that he died and my father does not know where exactly he was buried.”

This bit of family history inspired a scene in the book: When Odenigbo hears that Mama has died, he drives frantically in the rain to find her body and is stopped by soldiers. He gets home, to Olanna, and begins to cry.

“Where were you in 1967?”

Chimamanda’s first attempt at telling the story of Biafra was not in the grand scope of a novel but in the microcosm of a short story, also entitled “Half of a Yellow Sun.” It is told by a young woman, studying in Nsukka when the war begins, who returns home and watches her family struggle to hold itself together through devastating loss. A month before Purple Hibiscus was published, that short story won the David T.K. Wong Prize for Short Fiction. At the American award event, a professor, Obi Iwuanyanwu, said: “Given my knowledge of similar astounding young writers in history, I would make bold to describe her as a genius. I believe that Chimamanda, who was born seven years after Biafra, is destined to write the Great Biafran Novel.” He could not have imagined that she already was.

That short story — and two others, “That Harmattan Morning,” a 2002 BBC Short Story Competition winner, and “Ghosts,” a highlight in The Thing Around Your Neck — helped her test the enervating emotions that would envelope her writing the novel. It removed most of the anger she felt and taught her that, in fiction, distance is key.

She went to older people and asked them, “Where were you in 1967?” and her imagination did the rest. She looked at photographs from the war as she formed the skeleton of the narrative. Her uncles’ stories fed her description of the atmosphere at the front, but to recreate the mood of Biafra’s middleclass, where most of the primary and secondary characters are drawn from, she relied on books, chiefly the novels Chukwuemeka Ike’s Sunset at Dawn and Flora Nwapa’s Never Again.

It was Ph.D.-level research. The first draft was full of political events, recreating the grand climate of international diplomacy. But she knew how easily politics could overwhelm the human story, and her aim was to capture emotional truth: a thing rarely pre-known except when felt. So she pruned it, sieved it, cutting and re-writing, through four years and seven drafts, until it became the character-driven story that it is.

Chimamanda’s father told her that after the war, when he returned to his house in Nsukka, he found his books and shelves burned, piled in the front yard where he used to grow roses, and that his colleagues in the U.S. sent him books. She weaved this into the end of the novel, when Odenigbo and Olanna return to their house in Nsukka to see that their books have been burned and Odenigbo receives books with a note: For a war-robbed colleague from fellow admirers of David Blackwell in the brotherhood of mathematicians.

Placing Olanna and Odenigbo’s love story — and Richard and Kainene’s, too — at the center of the book was also a way to maintain its emotional beats, for readers to come away from it thinking not simply of the carnage of war but in larger terms of what it means to be human.

She based her central character, the dedicated Ugwu (“My name is not Sah. Call me Odenigbo” — “Yes, sah — Odenigbo”), on her grandparents’ help, a young man named Mellitus, but enriched his 13-year-old life with war-time teenage stories from her cousin Paulinus Ofili, who died a year before the book came out. She based Okeoma on the poet Christopher Okigbo, who enlisted in the Biafran Army and died in the war, and his collection Labyrinths. Alexander Madiebo’s memoir The Nigerian Revolution and the Biafran War informed the character of Colonel Madu.

The twins, Olanna and Kainene, are different sides of her, the gentility and the spikiness. Olanna’s former lover, Mohammed (“his tall, slim body and tapering fingers spoke of fragility, tenderness”), is a variation on the character in her play For Love of Biafra. In the play, Mohammed is in England while the war rages, and after Biafra surrenders, the heroine Adaobi tells him, “I am a Biafran first, a Biafran last, a Biafran always, don’t ever make the mistake of calling me a Nigerian again.” She used Richard — kind, sexually deficient Richard, a white male writer — to subvert the West’s entitlement to telling African stories.

The characters jump out, almost real. In a parallel world, Odenigbo might be living his vibrant Mathematician life in a university, a man “who trusted the eccentricity that was his personality,” “not particularly attractive but who would draw the most attention in a room full of attractive men.” The women are clear-headed. Olanna “wished she were fluent in Hausa and Yoruba. . . something she would gladly exchange her French and Latin for.” Kainene knew right away that “It’s the oil. . . They can’t let us go easily with all that oil.” And because Chimamanda wanted to be even realer, she wrote a scene where Ugwu, conscripted, joins in a gang rape.

To suit the story, she re-arranged things: the distance between towns, the chronology of conquered cities, and she put a beach in Port Harcourt and a train station in Nsukka. But every atrocity in the book did happen in Biafra, and it was overwhelming for her, knowing she did not have to make those parts up.

She cried, took walks, licked chocolates. She left Baltimore, where she was studying for an M.F.A. at Johns Hopkins, and wrote sections in Nigeria.

Not having experienced the war gave her distance, which would not have been creatively possible for someone who had seen the butchery firsthand. Yet to ascertain that she told their story with dignity and truth, she wanted two people from the war generation to read the book: her father and Achebe. But she was aware, too, that the generation that experiences trauma is barely the one that talks about it, that it is usually the people coming behind, and so she knew that she was really writing for her generation and those after.

“We must remember. We cannot forget. We must remember”

Half of a Yellow Sun shows the failed making of the Nigerian state. In the book’s lifetime, it has, in a country where history repeats itself, mirrored the resurgence of secessionist movements. In 1999, an Igbo lawyer, Ralph Uwazuruike, woke the ghost of Biafra when he formed the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (M.A.S.S.O.B.), looping Nigeria’s southeast into a frenzy. In the promise of a new state, fathers and sons left their shops mid-day to join great marches in Igbo cities, and on the days M.A.S.S.O.B. marched, cities shut down.

Half of a Yellow Sun was published in 2006. Three years later, Nigeria removed history from school curricula. Since M.A.S.S.O.B., new groups — the Biafran Zionist Movement (B.Z.M.), the Biafra National Youth League (B.N.Y.L.), and, most notably, the Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (I.P.O.B.), led by Nnamdi Kanu, a political economist who attended Nsukka — have since come up.

The government of Muhammadu Buhari, a retired general who fought in the war on the Federal side and later became military head of state, blocked the I.P.O.B.’s popular Radio Biafra, turning a fringe agitation into a mainstream movement, and more Igbo people embraced it. So began the heavy military presence in the southeast. This was 2015, and it was in this context that Chimamanda received her first Women’s Prize “Best of the Best” win for Half of a Yellow Sun. It was also the year her father was kidnapped, an 80-year-old man thrown into a car boot and held for three days, siphoning her faith in Nigeria.

Chimamanda has just told me about her father not finding her grandfather’s corpse when I begin to unroll this context. I ask her if, in light of his passing, she sees the leaving of the survivors of the war — “a generation at dusk,” as she described them in her account of his kidnap — as an irrecoverable loss of cultural memory. What urgency does she feel it has left the younger generation, the many millennials and Gen Z people for whom her novel was their first storified awareness of the war? How does she see her book now that young I.P.O.B. men take to the streets unarmed and are mowed down by the Nigerian military? How does it make her feel seeing her book’s relevance, its point that we never forget, continuously refreshed by these developments?

“It’s still very strange talking about my father now that he is gone, and” — she bends her head — “I am almost getting angry with you. It’s very unreasonable, but as you were saying ‘Your father passed,’ I wanted to say, ‘Whose father passed?’” She half chuckles, then furrows her brows to engage the question. “I do think that my novel and the neo-Biafran movement really represent two very different things. My book is about looking backwards. I.P.O.B. and the movements are about looking forward,” she says, and I realize that this question is one she has previously given thought to. “If I were asked to place Half of a Yellow Sun on a political pedestal, what I would write on that pedestal would be: ‘We Must Remember. We Cannot Forget. We Must Remember.’”

The I.P.O.B. sprang from a strong sense of increasing mistreatment and marginalization of Igbo people in Nigeria, “a very present phenomenon,” she notes. “But many people are still not versed in what happened in Biafra. I think that Biafra for this new movement is kind of an iconic thing they call upon, but the goal is to get somewhere in the future. That goal is not one that I don’t support, because increasingly, under Buhari’s government, I’m really now starting to see the basis for political ethnicity. I didn’t, I didn’t always — I do now. Half of a Yellow Sun is about how important it is to remember. I want every child in this country to know what the hell happened. If anything, it’s a plea for the humanizing of history.”

It distresses Chimamanda when people tell her that, until they read Half of a Yellow Sun, they had no idea what happened. It distresses her but also makes her happy because now they know. What she finds funny is a few people telling her that she had to have made some parts up — the gruesome, violent sections of the book. She always replied that they feel that way because they were “resisting accepting that our history is really f-ed up.”

The elongation of that “f-ed up” history, of ethnic marginalization and systemic dysfunction, led her to a reluctant but freeing place. “When I realized I didn’t have to love Nigeria, it was a very freeing thing for me,” she tells me. “If you ask what I think of Nigeria now, I don’t know. I think of Nigeria with a shrug. I don’t have to love Nigeria, but again, if I were honest, I would also say that maybe that position is one of self-protection, because if it were really true that I didn’t love Nigeria, why am I here? Why I am here and every day I’ll buy diesel? Why am I stressing, ‘Where are the vaccines for Nigeria’? Why do I go out and I just think, ‘My God, my people don’t have opportunities.’ Why, why, if I didn’t love Nigeria?”

(In June, four months after our conversation, Buhari’s government banned Twitter in Nigeria after the platform removed his tweet that threatened more violence on the southeast: “Many of those misbehaving today are too young to be aware of the destruction and loss of lives that occurred during the Nigerian Civil War,” it read. “Those of us in the fields for 30 months, who went through the war, will treat them in the language they understand.”)

She resents that negatives have come to be accepted as Nigerian, but she remains hopeful. “I really want this country to get better.” Then she lowers her voice, as if uttering the unthinkable: “And most of all, I think that it can be.”

IV.

“If something were not true to me, I wouldn’t do it”

Most of what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie does in her talks and essays is describe the world she wants to see. But in her fiction, she makes that world. She watches people, observing minute traits, making quick initial impressions, and, with her own skill of character affectation, brings bits of them into her fiction. Her novels are threaded by personal tropes, used not only as character templates but to outline her worldview of family and friendship.

There is the Strong Aunt: Aunty Ifeoma in Purple Hibiscus, Aunty Ifeka in Half of a Yellow Sun, and Aunty Uju in Americanah. The Influential Sister Figure: Amaka in Purple Hibiscus, Kainene in Half of a Yellow Sun, and, to a lesser extent, Ginika and Ranyinudo in Americanah. And there is the Good Man in Love: Father Amadi in Purple Hibiscus, Odenigbo in Half of a Yellow Sun, and Obinze in Americanah. Her central characters — Kambili, Olanna, and Ifemelu — deviate from the tropes but remain surrounded by their support. Such archetypal worldbuilding works because she avoids generalization and locates specificity even in the minor characters and arcs. Is this deliberate?

“No!” she bursts into laughter. “This is why I don’t like these conversations — see, this is the problem with why writers should never talk to critics. No, it’s not deliberate.”

She ponders the characters I tell her I preferred on first reading: Odenigbo and not Ugwu in Half of a Yellow Sun, Blaine and Curt and not Obinze in Americanah. “You know what I’m already sensing?” she says. “So the good people bore you.”

“No, they don’t bore —”

She squints in comic suspicion: “That means there’s a dark, dark thing in your heart.” She throws her head back and laughs, her afro a jiggling halo, and I think about how she describes Ifemelu: It was the laugh of a woman who, when she laughed, really laughed. “I love a good conversation of ideas,” she laughs. “I love a good argument.”

I ask her about another trope: her use of salons, hosted by Odenigbo in Half of a Yellow Sun and by Shan in Americanah, her avenue to bring characters together to argue and debate ideas. “It was also about my father,” she says, “and I’d read about these academics that sort of — this exuberance of the ‘60s, you know. And I think that there’s a part of me that romanticizes that, because it doesn’t really exist now. Even with my father’s friends, they would gather and talk, but were they really talking about ideas that would change the world? Not really. They were bemoaning, imagonu, SAP. But in the ‘60s, they were like” — and she, with a balled fist, slips into a persona halfway between Odenigbo and his sparring partner Miss Adebayo — “‘What is going on in Congo? We must liberate South Africa!’ So I really wanted to try and capture that in Half of a Yellow Sun. With Americanah, I can see, I can — see, I don’t like having this kind of conversation. The book I’m working on now — I don’t want to start thinking of ‘tropes,’ and I hate that word ‘trope.’ But go on.”

I point out an interview from 2013 in which she used the word. She bursts into laughter, “Wait, wait, wait,” and continues laughing. “Wait, wait, wait, I leaned what — wait, so, so, what tropes of mine did I lean into more?”

In her convergence of tropes, it is an unlikely character that has drawn scrutiny: Obinze. I tell her that most men say they don’t recognize Obinze and she nods that women have told her the same, too, accusing her of manipulating them into wanting such goodness in a man that just doesn’t exist. Obinze’s goodness, similar to Olanna’s in Half of a Yellow Sun, comes too close to her. A friend once told her: “Ifemelu is the person you wish you were and Obinze is the person you actually are.” She told Ebony in 2014: “Obinze is my idealized male self.”

In enriching even her secondary characters, allowing you see how each has their own story ongoing, she goes against a popular rule in creative writing: focus on the main characters.

When it comes to style, there is a lot in M.F.A. writing programmes that she disagrees with. She had written Purple Hibiscus in the flush of poeticity, but studying at Johns Hopkins and writing Half of a Yellow Sun, she, then still a rule-follower, listened too much to instructors and clipped her prose into short sentences, sacrificing style for brevity, settling for the power of her storytelling to do the job. It did, its balance of long and short sentences worked, and yet, even while knowing that anything more would have messed with the poignancy of narration, she looks back with faint wishes.

“Can I just say, I think, Purple Hibiscus, I” — she sings in threes — “am quite pleased — with my sentences. I think that it’s poetry.” I chuckle at her delight and she sings, “Thank you very much.” But when she opens Half of a Yellow Sun, “There are some places I’ll be, like, hmmm, very elementary.”

And so, in the lightness of Americanah, she went rogue, opening with a 62-word riff on the smell of American cities. “I’m glad that you noticed that first sentence,” she says, “and it was very deliberate on my part, but also honest. If something were not true to me, I wouldn’t do it. It came, I didn’t hold back, ordinarily I might have said maybe it’s too much, what would Raymond Carver say? No, I didn’t do that this time.”

“There was freedom,” I nod.

“Yes,” she says, “and because there was freedom, I could” — she moves into another musical tenor — “do the long sentence and be like ha ha ha!”

The freedom came from practical privilege: With Half of a Yellow Sun doing so well, she could afford to write a book that wouldn’t sell as well but that would satisfy her as long as it were true to her. What she didn’t foresee: Americanah selling two million copies in 29 languages worldwide within six years, and then beating some heavyweight bestsellers to win the “One Book, One New York” initiative.

I run through a stylistic evolution in her prose game, starting from the 2010 short story “Birdsong” and formalized in her 2017 rereading of Albert Speer’s The Third Reich, and I joke that it’s a showoff, and she chuckles, and says in Nigerian, “So someone cannot show off again? Every day, every day, dutiful daughter — some days, show off.” (In Notes on Grief, she writes: “A new voice is pushing itself out of my writing, full of the closeness I feel to death, the awareness of my own mortality, so finely threaded, so acute.” I wonder what this means for her newfound stylist spirit.)

It is also in Americanah that she uses more untranslated Igbo. She said in the Ebony interview: “What was more important, for the integrity of the novel, was that I capture the world I wanted to capture, rather than to try to mold that world into the idea of what the imagined reader would think.” Where Achebe introduced Igbo philosophy to a global readership, Chimamanda has, novel by novel, acquainted that audience with the language itself.

Chimamanda looks back at her M.F.A. experience at Johns Hopkins with gratitude for the space and stipend. “Alice McDermott was lovely,” she says of the novelist, one of her teachers. But she wishes the focus was “a bit broader.” The things some of her cohort members had problems with were things she looks back and realizes were the most interesting bits. She was the only Black student in her cohort, and very few of her classmates and faculty attended her reading when Purple Hibiscus came out. It felt strange to her that it was her own undergraduate students, and not the M.F.A. programme, who organized the reading. A professor told her he didn’t believe the novel because it was “too familiar” to him; he expected the stereotypes in The Economist and on CNN. She also didn’t like the stringent rules of “Show, don’t tell,” how they were constantly being told to curtail themselves, but she bought into that. Minimalism appealed to her to a certain extent, but she remembers reading David Means, whose sentences can stretch to a page.

And yet even after the success of Half of a Yellow Sun gave her freedom, and she started her workshop in Nigeria, she continued in the M.F.A. tradition. “I think the people who went to my workshop in the first two years and the people who’ve gone now, they’ll tell you it’s a different person. Now I just feel, like, no, we need to let the art speak to us.”

Which was why Binyavanga was so essential to the workshop. “I wanted to give people this: you have me, rule-follower to an extent, and then you have Binyavanga. You could see I had the deepest respect for him and he had the deepest respect for me, so it shows what is possible in literature.”

Which is why she asks her workshop people to also read white male authors. “When young people come and tell me, ‘I’m not reading any white men,’ I’m like, no, you have to. First of all, there are some lovely books by white men. But even to understand what you don’t like, you need to know it, to understand why you don’t like it. You need to be familiar with what they call the ‘Western Canon’ in order to criticize intelligently.” In the same breath she shifts into killer mode: “Austerlitz is so brilliantly cold, and I remember reading it — I quite like the sentences — and I thought, My God, I would recommend therapy for this writer.” (She reads male writers with a penknife as page-marker: Ask V.S. Naipaul, whose A Bend in the River gets torn into in Americanah and about whose The Masque of Africa she said, “I started reading, then I stopped halfway — it was just bad.”)

She is in critic mode now. “I read with my head but I also read with my heart. I find that there is an emotional awkwardness you see in white male writers and that we forgive. Not only do we forgive them, we call it greatness. Think about how many women would write the way they write and be called great? They wouldn’t. I went through a period when I sat down and read quite a number of Great White Men.”

Her belief in the diversity of African stories was why when Teju Cole, then a new writer, sent her a copy of his Lagos novella Every Day Is for the Thief, she was excited that someone was doing something different. She liked the book, and, when his novel Open City came out in 2011, co-hosted a luncheon with Random House to introduce him to American journalists.

In publishing, a word from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie carries weight, of course. She liked then new writer Jowhor Ile’s short stories, talked him up in an interview, and his novel became anticipated. For Harper’s Bazaar, she profiled the rising 23-year-old artist Tonia Nneji. Three years ago, after Barnes & Noble honoured her with its Writers for Writers Award, she invited the novelist and McSweeneys editor Dave Eggers to teach at her workshop, and when he picked five stories for publication in the magazine, she wrote an introduction. This year, Ile and one of writers published in McSweeneys, Adachioma Ezeano, won O. Henry Prizes, for the anthology she guest-edited.

In its 14 years, the workshop, first named after her former Nigerian publisher Farafina and later renamed after her Purple Hibiscus Trust, has seen over 250 writers pass through it.

“My whole life has been one where difference is normal”

The workshop was also the source of her first public controversy. A 2013 interview she granted — in which she, rightly, said that “the Caine Prize is not the arbiter of the best fiction from Africa” and affectionately called one of the prize’s shortlisted writers, a protégé and graduate of her workshop, “one of my boys” — drew furious responses. Half of the backlash was spurred by the shortlisted writer resenting being called “boy”; the other half was to her saying sarcastically, in response to a question about where she goes to read “the best new fiction from Africa,” that “I go to my mailbox.” It was the start of a bewildering phase for her, in which, the more famous she became, the more her offhanded comments snowballed into news.

In 2014, she criticized Nigeria’s anti-gay law, one of very few public figures to provide much-needed mainstream allyship for the country’s embattled L.G.B.T.Q. population. It signaled to a great number of conservative Nigerians, already rankled by her preaching of feminism, that she was Trouble, and they duly made her a scapegoat for sexist frustration. They accused her of saying that women who wore attachment lacked self-confidence. They lashed out because she refused to be addressed as “Mrs.,” to have her identity be subsumed by marriage. They chided young feminists as “Daughters of Chimamanda.”

“It was not unexpected when the lash began,” Adachioma Ezeano, the O. Henry Prize winner, told me. “She has, on the basis of her gender, been a target for men. It’s the idea that a woman must be hushed, otherwise she should ready herself to be cracked open. Clamp down on vocal women for doing what their male counterparts would be applauded for. They expect her to shut up and write. But she is powerfully vocal, a reincarnation of pre-colonial women.”

The more comfortable Chimamanda got in the spotlight, the sharper her clapbacks became. At the Night of Ideas in Paris, the interviewer asked her if there were bookshops in Nigeria, and she nodded in incredulity as the crowd murmured, and she said, “I think it reflects very poorly on the French people that you have to ask me that question. I mean, it’s 2018.” In the same interview, though, asked her thoughts on postcolonial theory, she said with a straight face: “I don’t know what it means. I think it’s something that professors made up because they needed to get jobs.” The reaction was predictably mixed, excitement for the clapback, bewilderment at the comment, with academics pointing out that, as a successful writer with an M.A. in African Studies whose books are taught as cornerstone postcolonial literary texts, she was knocking at the ladders that lifted her.

And then, in a Channel 4 News interview in 2017, she was asked, “Does it matter how you’ve arrived at being a woman, for example, if you’re a trans woman who grew up identifying as a man, who grew up enjoying the privileges of being a man, does that take away from becoming a woman, are you any less of a real woman?”

She nodded as the journalist spoke. Then she said, “So when people talk about ‘Are trans women women?’ my feeling is trans women are trans women. I think if you’ve lived in the world as a man, with the privileges the world accords to men, and then sort of changed, switched gender, it’s difficult for me to accept that then we can equate your experience with the experience of a woman who has lived from the beginning in the world as a woman and who has not been accorded these privileges that men are. I don’t think it’s a good thing to conflate everything into one. I don’t think it’s a good thing to talk about women’s issues being exactly the same as the issues of trans women. What I’m saying is that gender is not biology, gender is sociology.”

The backlash was quick, wide, furious, and deep. The words held aloft: “Trans women are trans women.” Why did she not use “cis” to describe non-trans women?

She clarified on Facebook: “Perhaps I should have said that trans women are trans women and cis women are cis women and all are women. Except that ‘cis’ is not an organic part of my vocabulary”; later posting: “To say this is not to exclude trans women from Feminism or to suggest that trans issues are not feminist issues or to diminish the violence they experience — a violence that is pure misogyny.” Then she said, “Of course they are women, but in talking about feminism and gender and all of that, it’s important for us to acknowledge the differences in experience of gender. That’s really what my point is.”

The backlash persisted, and in 2018 she referred to it as “the trans noise,” and in 2020 said that an essay on sex and gender by J.K. Rowling, which sparked controversy about trans women, was “perfectly reasonable,” and the backlash flared again. Since her first comments, she has needed extra security at book launches.

“What’s interesting to me is this is in many ways about language,” she said then, “and I think it also illustrates the less pleasant aspects of the American left that there sometimes is this is kind of language orthodoxy that you’re supposed to participate in, and when you don’t there’s kind of backlash that gets very personal and very hostile and very closed to debate.”

Her comments on trans women cost her relationships. (Four months after our interview, Chimamanda would publish, on her website, a viral piece titled “It Is Obscene”; it named no one but described the actions of two of her workshop graduates, tying their behaviour to social media sanctimony and cancel culture.) Seated on her couch, she says quietly, “I cannot tell you how deeply hurt I was.”

She switches to her usual assuredness: “I said to myself, ‘I need to do what I tell people: if somebody criticizes you, you have to look inward.’ I said, ‘Is there a blind spot?’ In all of this, I’ve read every trans memoir published. I’ve read everything about transgender ideology. I went because I needed to understand what was going on with the reaction. I genuinely didn’t. Partly also because I’ve never really been part of a certain kind of academic feminism in America. What I am is really a storyteller. I’ve tried to read a lot of feminist theory. I am a very clear thinker. When I wrote that on Facebook, I was willing to start saying ‘cis women,’ because if ‘cis’ just meant you’re not trans, okay. When that happened, there were lovely trans women who wrote to me, through my manager. And I think there’s a generational thing, they were mostly older people. They wrote to me very lovely letters, saying, ‘We’re sorry that you’re going through this, we know what you mean,’ and I really appreciated that. Having read a lot, perhaps too much” — she laughs — “I think I became slightly obsessed; all the newspapers I read, anything about transgender, I’m reading it.”

I ask her about her childhood, being a girl who never felt she fit in with other girls, and she tells me the reason she has not used “cis” to describe herself: “Gender ideology says that ‘cis’ means that your gender matches the sex you are born with. That’s not true for me. So if we go with gender ideology — then I’m what?” Perhaps she feels the time is right to address this part of her life. “I’m actually writing something now,” she says, “because, just as I said, since June 10, I’m just like, no, I need to.”

In her reading on the stories of trans people, she has also been thinking about anti-lesbian homophobia. “There are lesbians who are still trying to carve out a space to be, and suddenly you’re telling them that they cannot define themselves? Mba nau, no, no, no, what is that? For me, inclusion means ‘make room for everybody.’ The problem with the liberal left in America, and I have a huge problem with that, is that on one hand they advocate to embrace difference but actually the response to that is to squash difference. Because my whole life has been one where — I think difference is normal, that’s how I was born.”

Back in 2017, as she sought to understand why her words were considered offensive, newspapers were calling her agent, asking if she was “ready to change her mind now.” It felt, to her, like she was suddenly in a reeducation camp. A year later, though, she was winning the PEN Pinter Prize for how “she refuses to be deterred or detained by the categories of others” and “guides us through the revolving doors of identity politics, liberating us all.”

While We Should All Be Feminists has sold 750,000 copies in the U.S., Chimamanda has said that being considered a “feminist cheerleader” makes her cringe. “I don’t feel that I’m the authority on feminism and I don’t necessarily want to be,” she said in that controversial interview. “I think of myself as a storyteller who from time to time will talk about what she’s passionate about, which is feminism. Feminism’s ultimate goal is to make itself redundant, to get to a world where we no longer have to be labeled feminist because the world would be gender-equal. And for that to happen, we need to have as many people onboard as possible.”

“What I learned is,” she tells me, “(a) a complete lack of patience in orthodoxy and then (b) you know what, I think I’m a person for whom my hurt comes out as anger. I had a wise woman once say to me, ‘You need to acknowledge when you’re hurt. Let your hurt be hurt.’ She said, ‘It’s easier for you to be angry,’ and I think it’s true. So I was hurt, and it just came out as rage, and that rage is bubbling up right now.”

“Since June 10, there has been sort of like a gash in my worldview”

It is 8 p.m. Our allotted interview time ended at 6:30 p.m. and I have been in her home for two hours and 11 minutes now. Her chef, G., returns with a tray of glasses of orange juice, and she, before she sips hers, asks me, “Are you sure you don’t want more?” She has barely kept the glass when she exclaims, looking at her phone. I have taken up time for another appointment. I apologize and she assures, “No, don’t apologize.” And she keeps her phone. In the two more hours we talk, her demeanour is still permeated by humour, a willingness to follow the trail of sarcasm for a good laugh. “Wait, wait first,” she laughs to a comment I make, “there’s something there, who is that shade meant for?”

She is talking about rage and love when a video call comes on the i-Pad on the table. “Ohhh, sorry, sorry,” Chimamanda says, and calls for her daughter. “She has a phone call. She has to do the video with her friend.” She turns to the i-Pad. “Hel-lo,” she beams at the excited child in the screen, and she gets up, towards the dining table. Her daughter runs in and Chimamanda tunes: “Time to call her back.” And gives her the i-Pad.

“Where were we, in our gossip?” She smiles. “Ike agwugokwam, biko. I’m really slow now, imagonu, ndi ogbanje no m n’isi na-agwa m okwu.” I chuckle at the imagery of ogbanje spirits whispering in her head, making her tired.

But she continues, hitting several points: “There’s a kind of grasping, calculating energy that just shocks me. When you become successful, people see you and think, ‘What can she do for me? What can I gain from her?’ But when you do it in a way that’s — ruthless.” She shakes her head. “People are not allowed to learn. There’s an automatic assumption that not only should you know the orthodoxy, you should abide by the orthodoxy, there is the assumption that anybody who doesn’t has ill will. I like to see young people stand up for something. I think, on social media, there’s an element of performance, then you meet them in person.”

Success makes people unreachable, super success makes them unbroachable, but Chimamanda has been open in talking about everything, so I ask her a question I have had in mind for years: “Do you feel untouchable?”

“Nooo,” she says, with a thrust of shoulders.

“Not personally, I mean professionally.”

“No,” she says. “You see, this is actually an interesting question. I am now learning from my own experience. There are certain judgements I used to make about other people. So maybe a famous actor or political figure is being interviewed, and I’m looking at them as, ‘Ah, where you are nau’ — and they talk about feeling a certain kind of vulnerability and I’m, like, ‘Come on!’”

Sometimes, when she attends events, well-meaning people tell her not to say anything controversial. “There is a kind of love that results in great resentment,” she tells me. “Since June 10, there has been sort of like a gash in my worldview.”

Chimamanda is a bard of individuality. Her unspoken battle, I find, is to reclaim her path from the public. It is to rearrange any ideas of the conventional successful, beloved woman expected to speak only the agreeable, to replace that with a real human being who will not stifle herself to please observers. Her unspoken battle is to re-place herself.

She insists on difference, nuance, complexity. She knows, for example, that her first literary hero Enid Blyton was racist, but she will not shed the joy of her childhood because of that. “The response to bad speech,” she has said, “is more speech.”

A call comes on another i-Pad and she looks at her daughter. “Papa is calling. I ji i-Pad?” She has no i-Pad with her, so she comes to take her mother’s. “Does she look like me?” Chimamanda asks me. I am aware that she has lovingly complained in public that her daughter used to instantly run to her father whenever he returned from work, leaving her the mother puzzled. I grin, measuring my words. “Tread very carefully,” she says with a mischievous smile.

“The very best that the literary community has to offer”

Last November, a week after Donald Trump was voted out as U.S. president, The New York Times asked Chimamanda to write the paper’s lead review of Barack Obama’s hefty memoir A Promised Land. Obama is “as fine a writer as they come,” she wrote. “And yet for all his ruthless self-assessment, there is very little of what the best memoirs bring: true self-revelation.” Her analysis, in how it doesn’t let even a man she seriously admires off the hook — a man who has called her “one of the world’s great contemporary writers” — demonstrates why her internationalist voice, the informed, scrutinizing perspective of an outsider unapologetic about her allegiances, is highly sought after.

It was why, upon Trump’s election in 2016, the BBC put her on a panel to argue if the man would lead with the divisive rhetoric he campaigned with, and when the other panelist said that the rhetoric was not racist, she replied, “I’m sorry, but as a white man, you don’t get to define what racism is.” It was partly why Hilary Clinton requested to be interviewed by her onstage after her 2018 PEN America lecture, and then she asked the former presidential candidate, Secretary of State, and First Lady why her Twitter bio led with “wife,” setting off alarmed reactions, until Clinton changed the bio. It was why PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel said afterwards: “When we need the very best that the literary community has to offer, we are grateful we can turn to Chimamanda, and she never disappoints!”

It was also why, later that year, Michelle Obama, who previously edited her for MORE and to whom she wrote a beautiful tribute after leaving office, asked her to moderate the London stop of her Becoming book tour. And it was on that stage that the Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle saw her and, the following year, put her on the September cover of British Vogue.

Chimamanda herself understands the humanity she brings to political conversations, and so, earlier this month at the Theatre der Welt Festival, she asked the German Chancellor Angela Merkel about the Nigerian government’s claim of a contract with Siemens to bring electricity in Nigeria. “I will get back to you,” Merkel said, “you will get your answer.”

“Please come to Lagos,” Chimamanda said at a point.

“If you will receive me, I will come,” Merkel said.

“It’s done,” Chimamanda said.

Hers is a completely Nigerian voice, embodying in attitude the full potential of the country’s soft power. It is an audacity that, on the global stage, only Nigerians carry with ease, and in being an exceptional Nigerian, it would not escape her that she says with casualness what many people wish someone would. That voice ensured that her #ProjectWearNigerian added attention to the country’s fashion industry, coupled with her Boots No. 7 endorsement being a radical, political move that a British brand tapped a dark-skinned writer to front a campaign.

Unlike most Afropolitan writers of her generation, Chimamanda has never wavered in her commitment to Nigerian affairs. She criticized and fictionalized former president Goodluck Jonathan — during whose administration she was honoured with a Global Ambassador Achievement Award — as she later, twice, would Melania Trump. She spoke up when the Oba of Lagos threatened Igbo residents with death in the lagoon if they didn’t vote for his governorship candidate. And she spoke up again when, under Buhari last year, End SARS-protesting young Nigerians were killed in the infamous Lekki Massacre.

In Nigeria, she is freely critical. But once outside Nigeria, she represents, becomes fiercely protective. She always believed that leaving a country is one’s process of finding themselves. That is why it was important to her that Ifemelu, the heroine of Americanah, returned home.

Chimamanda’s liberation in Americanah had an industry-wide effect. Marlon James has said that the novel, in its “post-post-colonial” stance, changed attitudes in publishing towards novels by and about non-White people.

Lexy Bloom, her U.S. editor at Alfred A. Knopf, told me why her work resonates in America. “Chimamanda writes about race and gender in a way that is both trenchant and accessible,” she said — “her choice of subject, her ear for dialogue, her excellent powers of observation, and her profound ability to go succinctly to the heart of an issue with sharp analysis and brilliant wit.” Bloom points out Ifemelu’s blog post in Americanah, “To My Fellow Non-American Blacks: In American, You Are Black, Baby,” as a “perceptive view of race [that] is eye-opening to many Americans.”

Years before the election of Trump, the death of George Floyd, and the globalization of Black Lives Matters protests, Americanah, Bloom said, “spelled out the hypocrisy, racism, and stratification that defines American politics.” The novel is, she said, “one of the most prescient, transparent books about race in the U.S. to be written in the 21st century.”

Every one of her novels, in expanding her subject matter, broke down a wall in publishing. Purple Hibiscus proved that there was an international market for African realist fiction post-Achebe. Half of a Yellow Sun showed that that market could care about African histories. The novels say: We can be specific in storytelling.

In the U.S., her post-post-colonial approach has sold over two million copies. “Her books are serious; they are also great big love stories,” Bloom explained. “She has shown the publishing community that you can tackle these issues in works that meet with critical and commercial success.”

She agreed with Marlon James. “It is in part thanks to Chimamanda that publishers are now eager to publish a multiplicity of African stories — stories that speak of homosexuality, of feminism, of family drama; stories that cover a variety of genres, from romance to sci-fi and fantasy; from commercial to literary fiction — stories that do not define themselves purely by their relationship (or lack thereof) to the US or Britain. If that isn’t liberating, then I don’t know what is.”